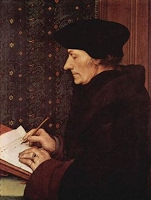

12. Erasmus/De Liefde

Lecture by Hans Brinckmann at the Tokyo National Museum, under auspices of the Japan-Netherlands Society. November 12, 2008

What was Erasmus doing on the stern of "De Liefde"?

The strange tale of the sole surviving part of the first Dutch ship to arrive in Japan

- The commissioning and journey of De Liefde, as part of a fleet of five ships that sailed from Rotterdam on 27 June 1598

- What is the function of a figurehead? And a decoration of the stern? Examples.

- Who was Erasmus? Why was Erasmus’ wooden carving attached to the ship?

- What happened to the Erasmus sculpture in Japan?

- he historical importance of the Erasmus carving

1. The journey of the De Liefde and the other ships

The known history of the De Liefde begins in 1598, four years before the establishment of the V.O.C., the Dutch East Indies Company, in 1602. Two entrepreneurs in Rotterdam, a merchant and a banker, commissioned and dispatched a fleet of five ships in the direction of “Asia” – probable destination: the Moluccan Islands – to conduct trade. They carried a cargo of woven textiles, mirrors, spectacles, glass beads, iron and muskets. But the main goal was to bring back spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon, and especially pepper, for which there was a constant high demand, for use as flavorings and to preserve food. Spices were also believed to offer protection against the plague, which had been raging in Europe since the Middle Ages.

The ships' names represented Christian concepts: Hoop, Geloof (Faith, or Belief), Trouw (Faithfulness, or Loyalty), De Blijde Boodschap (Good News, or the Gospel), and De Liefde (Charity). The fleet set sail from Rotterdam on June 27, 1598. The planned route – known to the senior officers but kept secret from the crew – was not the customary one around the Cape of Good Hope but through the Strait of Magellan, around the southern tip of Chile, notorious for its many shipwrecks.

De Liefde's was originally called the Erasmus. The name was apparently changed so that it would fit in with the biblical theme of the fleet. Of the five ships, only De Liefde would make it to Japan. The Hoop was the flagship, with Admiral Jacques Mahu as commander and William Adams as first officer or "pilot". After 3 months, as the fleet passed the Cape Verde Islands off the west coast of Africa, Admiral Manu died and a reshuffle of command took place, resulting in Adams being transferred to De Liefde. That would prove his good fortune. It was only then that the crew was informed of the ship's further route.

Even before the fleet reached the Strait of Magellan, most of the original combined crew of 507 had died from scurvy, fevers and hunger. The passage through Magellan was unimaginably rough, taking from April to August 1599! One of the ships, Geloof, gave up and returned to Holland. Another, Blijde Boodschap, was captured by the Spaniards (against whom the Dutch were fighting for their independence) and most of the crew slain. Trouw set off on its own and reached the Moluccan Islands, but it was captured there by the Portuguese and its crew murdered.

Halfway up the coast of Chile, De Liefde and Hope caught up with each other. They both had managed to restock their provisions and were ready to make the Pacific crossing. But because De Liefde's cargo consisted mostly of woollen goods it was decided to head for Japan where the cooler climate might help them sell their wintry merchandise, and obtain Japanese silver, porcelain and lacquerware.

Somewhere in the middle of the Pacific a heavy storm hit the ships, and the Hoop went down with all souls. De Liefde now continued the journey alone, which took another five months. At last, with only 24 of its crew of 110 still alive, and only 6 or 8 of them able to stand, the ship dropped anchor off the coast of Bungo in Kyushu, the present-day Usuki in Oita Prefecture, on April 19, 1600. Among them, besides Adams, was Jan Joosten, later to be given a tract of land. Yaesu, near Tokyo Station, is a corruption of his name.

Portuguese Jesuits accompanied Japanese officials taking custody of the surviving crew members (six of whom soon died) and urged their execution as they were 'pirates'. But Ieyasu Tokugawa – the Lord of Mikawa who was in Osaka at the time to exert his power over the Toyotomi clan, weakened after the death of their great leader Hideyoshi two years earlier – ignored their demand and ordered the sailors' imprisonment at Osaka Castle. There he met three times with William Adams, who apparently impressed him, especially after Adams arranged to release the ship's 19 bronze cannon and accompanying ammunition to Ieyasu. It is believed that these weapons helped Ieyasu win the decisive battle of Sekigahara later that year, which established him as de facto ruler of all Japan.

2. What was the function of a figurehead, and of the Erasmus sculpture on De Liefde's stern?

The history of the figurehead goes back to the Phoenicians. The prows of their oared galleys featured wooden carvings that depicted animals and deities. The Chinese and the Egyptians painted eyes (oculi) on the bows of their vessels, so that they might find their way across the seas.

From the 14th century onward major European nations vied with each other for supremacy of the sea, including Spain, Portugal, Holland and England, and the powerful city states of Genoa and Venice. A figurehead often adorned the bow of their vessels, increasingly so from the 17th century onward.

Weather played an integral role in the fate of ships and sailors. It was believed that a ship couldn't sink as long as the figurehead remained attached. On land there was a belief that if during a fierce storm a woman bared her breasts, the storm would abate. This is why bare-breasted female figure are often seen as ships' figureheads.

As the carvings grew more elaborate, they increasingly also served to scare away enemies and pirates. Thus the figureheads came to have the dual purpose of protection and intimidation.

What about the Erasmus sculpture? It was not a figurehead (boegbeeld in Dutch) which is fitted to the bow of the ship, where it can best fulfil its dual function. At the time Dutch ships did not feature figureheads, perhaps because of the design of the ships, or on account of the frugal habits of the Calvinist Dutch. Besides, the Dutch were more interested in commerce than war. So De Liefde had no figurehead. But it did have Erasmus – on its stern.

3. Erasmus, a brief biography

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus was born in Rotterdam in 1466 or 1469 as Gerrit Gerritszoon, the son of a physician's daughter and a man "who became a priest." He apparently later adopted his Latin name. Although almost certainly illegitimate, his parents gave him the best possible early education until they both died from the plague in 1483 when their son was still a teenager. His guardians then arranged for him to be accepted by a monastery, where eventually, and much against his wish, he was ordained into the priesthood, aged 25.

His true interests were scholarly, and he grew into a fierce critic of the excesses of the Church. He greatly admired Martin Luther and corresponded with him on vital questions of doctrine. Yet he did not join the Reformation and never left the Church, though the Pope eventually granted him dispensation from his religious duties to pursue his study of Latin, Greek and Humanism.

Erasmus studied and worked in Paris, Cambridge, Turin, Venice, Louvain, Rome (briefly), Freiburg in Germany, and Basel, gathering fame as a great scholar renowned for his independence and clarity of mind, epitomizing the New Learning that characterized the Renaissance.

Among his most famous works in Latin or Greek are the Adagia, a vast collection of sayings and proverbs going back to antiquity; The Praise of Folly, a satirical attack on the Catholic Church and popular superstitions; several other works aimed at revitalizing the Church; and Greek and Latin versions of the New Testament, which became the basis for translations into English, German and other languages.

He died in Basel in 1536, still a Catholic, but he was buried in Basel Cathedral, which had become a Protestant church when the whole city had joined the Reformation.

Why was Erasmus' figure on a ship's stern?

This is an intriguing question. The sober image of a Humanist scholar is not what one would expect to find on the bow or stern of a ship. True, Erasmus had been a famous figure, whose close friends included Thomas More and the painter Albrecht Dürer. But he was no busty mermaid, nor some mythical god. What's more, he was a Catholic, at a time when Holland had rejected Rome and become solidly Protestant. So why would a Protestant city like Rotterdam, where the ships were built, chose a Catholic scholar to adorn one of its ships?

I haven't come across any answers, but I would like to suggest two possible reasons. First, while a devout Catholic, Erasmus had been a severe critic of the Church, which tolerated his attacks during his lifetime but banned his books after his death. So Rotterdam had every reason to be proud of its famous son, though he only lived there for the first four years of his life and never returned. A stone statue honoring Erasmus was erected on Rotterdam’s market place in 1563 but destroyed by Spanish troops and thrown into the water. It was replaced by a wooden statue and, in 1596, once again by a stone one. So when De Liefde and the other ships were outfitted for their voyage two years later, Erasmus was (still) very much in the focus of Rotterdam's city fathers.

To this day, Rotterdam misses no opportunity to celebrate his life and legacy in the naming of institutions, projects and places. Examples: Erasmus University; Erasmus Medical Center; Erasmus Society; Erasmus Bridge. Elsewhere too Erasmus is an often invoked name. The Erasmus Student Exchange Programme of the EU is a recent example. There even is a robot called Erasmus in the Legends of Dune series, and an Erasmus song, on You Am I's 8th album, Dilettantes.

The second reason for his image on the ship might be that his name was associated with St. Erasmus of Formiae (Italy), a Christian saint and martyr who died around 303, also known as Saint Elmo. He was venerated as the patron saint of sailors, probably as he is said to have continued preaching even after a thunderbolt struck the ground beside him. This prompted sailors, who were in danger from sudden storms and lightning to offer him their prayers. The electrical discharges at the mastheads of ships were read as a sign of his protection and came to be called "Saint Elmo's Fire".

4. What happened to De Liefde and the Erasmus sculpture?

Very little is known about the fate of De Liefde after it arrived in Bungo. One account states that on orders of Ieyasu, the crew sailed De Liefde to Edo, where, rotten and beyond repair, it sank.

For more than three centuries nothing further was known or discovered. Then, in 1920, a Japanese scholar, Dr. Naojiro Murakami, examined an unusual sculpture that formed part of the treasures of the Ryuko-in in Sano City, Tochigi Prefecture. It was known there as “Katekisama”, which has been variously explained as referring to his priestly robes and the scroll in his right hand (perhaps a catechism?) and as a corruption of the mythical Chinese inventor of shipbuilding. Murakami identified the sculpture as the "figurehead" of De Liefde. He arranged to have it moved to the Tokyo National Museum, where it has been on permanent loan ever since. A photograph of the figure was displayed at a Catholic exhibition in Rome in 1926. On seeing the photo Dutch scholars concluded that it was not a figurehead but a "hekbeeld", meaning a decorative image attached to the ship's stern.

Once, perhaps twenty years or more ago, I had a chance to see "Erasmus" here, in this museum, displayed as part of a collection of Buddhist sculptures. And now, thanks to the efforts of the ladies of the De Liefde Club within the Japan-Netherlands Society, it is on display again, for a short period, in honour of the Nederland in Japan 2008-2009 celebrations.

5. The historical importance of the Erasmus sculpture

No doubt this "Erasmus" sculpture is a treasure of the highest order, in that it uniquely represents the very beginning of Japanese-Dutch relations at a time when Holland was exploring the world while fighting its 80-year war of independence from Spain. It is also the sole surviving tangible symbol of the great maritime and human drama that was the long journey of the ship De Liefde, and the historic importance of its arrival in Japan in the very year that the country, long torn by civil war, was unified under one ruler, Ieyasu Tokugawa.

So it seems entirely appropriate that the Japanese government has designated the Erasmus sculpture an Important Cultural Object.

Now before we go and meet the great man in person, I will gladly try to answer your questions.