You wouldn't guess it from seeing the year-end crowds filling the stores and cafes and restaurants all over Tokyo, and many places beyond, but many Japanese seem to be pessimistic about the future.

The gloom is not normally evident from behavior or expression. Not burdening your fellow citizens with your own internal feelings is a time-honored aspect of Japanese etiquette still commonly observed except perhaps by a section of the free-living young. The dark thoughts are largely carried mutely, often perhaps subconsciously. They are unquantifiable and abstract in that they do not (yet) impact daily life, except of course for the destitute and the long-term unemployed. Yet the signs of a pervasive pessimism abound, and they sometimes surface at the most unexpected moments. In early January I attended a small gathering of ladies celebrating the New Year around a table full of simple osetchi dishes lovingly prepared by our hostess, a widow in her eighties living alone in a small house. The other guests were a dressmaker and a senior nurse, both around 60. After some small talk about the food and the weather, the conversation turned to Japan and its "growing crisis." The feeling among the three was that Japan's future was bleak. It will be overwhelmed by China, maybe even become part of China. I disagreed, pointing out that as an island nation Japan would always be independent, "like Britain." But they said China's power would be exerted in other ways, through heavy financial investment, taking over Japan's markets, massive tourism, and "bullying." They added that Japanese didn't have the guts to fight that kind of treatment, and that the younger generation in particular was "too soft" to resist. Besides, China's population is growing, while Japan's is shrinking - though the nurse thought in the long run that would work out to Japan's advantage. "Once our generation is gone, it will be much easier for those who come after us as they won't have the burden of caring for a disproportionate number of old people. Also, the smaller population will place less stress on available land and resources." The younger two women agreed that the new government of the Democratic Party of Japan can do little to stem the tide. "They were not elected because we thought they could, but because we were fed up with the LDP," was their verdict, an opinion that seems fairly wide-spread. Our hostess offered that the DPJ is wrong to mess around with the US-Japan alliance, as it is the only - albeit weakening - source of strength in Japan's looming confrontation with China. "It's all thanks to the US that we had a good life since the war. Imagine what would have become of us if the Americans had not stopped the Russians from invading Japan! Now the danger is from China." The media often reflect similar opinions held by commentators and academics. A New Year's Day article in The Japan Times quoted Kazutoshi Hando, a historian, as follows: "This century is perhaps China's century. America's sole imperialism has come to an end. In that context we must really think hard now what course of action Japan should take to survive." He added that the Japanese have not been engaged in diplomacy ever since it quit the League of Nations in 1933 and throughout the post-war period. He predicts "40 years of doom" for Japan.

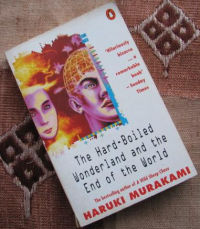

Another article, written in July 2009 by Kazuo Ogoura, the president of the prestigious Japan Foundation, examines the phenomenon that over the past "10 or 20 years" the Japanese people as a whole have become "domestic-oriented" or "introverted." The writer ascribes this trend to the rapid decline of Japan's industrial and economic power, which is gradually being replaced by the "soft power" of the "literary works of Haruki Murakami, manga, animation, costume play or the postmodern sensibility innate in otaku [geek] culture." He concludes that Japan is in the "transitional process of shifting from the quantitative to the qualitative." Far from exhibiting a "shrinking spirit" Japan is redefining itself so that it can make "a new appeal to international society." I applaud Mr. Ogoura for offering a positive interpretation to certain new aspects of Japanese society and culture that are often placed in quite a different light. Yet the problem with comments such as these is that they continue to refer to "Japan" as a monolith, rather than recognizing its growing diversity in which there is a place for both the advanced technology and superior quality of its industrial base, and the creative products of its gifted artists and designers. And, in addition, for a third sector offering educational, financial, architectural and other professional services to a sophisticated international clientele. The same comment could be made with regard to the three ladies' opinion that Japan's future is bleak. Japan's future is neither bleak nor brilliant. The country's character is growing more complex, and therefore more difficult to define. It can no longer be pigeonholed as an "industrial power" (or the Japanese as "economic animals") nor is it turning into a weird land inundating the world's shores with a tsunami of cartoon characters and infantile fashions. Japan is turning into what many Western countries became long ago: a multi-faceted society. What is needed therefore is not an effort to give it a convenient new label so that it can continue to satisfy those preferring to think in simplistic, catch-all concepts, but a positive recognition that the country is finally - if slowly - entering true maturity, complete with all the infuriating contradictions that such a complex state entails. To help people adjust to the changing character of Japanese society it would help if they are taught to place less reliance on "those in charge" - government, employers, parents - to take care of them. Instead, the emphasis must shift to individual, personal definition of goals and responsibilities, and education tailored to stimulate and help shape such personal choices within the greater context of a well-functioning social order.

Crucial to the success of this process is the building of self-confidence through communication with others. Rika Kayama, a well-known commentator on social issues, notes that over the past decade "there has been a sharp increase in the number of people suffering from depression" as they could quickly learn "that there were countless other people who were 'better' than themselves in the world just by checking out the Internet." Young people increasingly isolated themselves from society. Children spent long hours on their mobile phones, instead of communicating with their family. "Individuals maintain shallow relations with others," is her conclusion. It is to be hoped that wise opinion leaders - be they from government, academia or the ranks of inspired writers and philosophers - will go beyond identifying the existence of the gloomy mood, and instead point out ways in which people can lift themselves above it. Like it or not, we all have to accommodate ourselves to the gradual, but fundamental, shifts in society, and strive to find a new role for ourselves. |

© 2010 Hans Brinckmann